George Mason

|

“That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent natural Rights… among which are the Enjoyment of Life and Liberty, with the Means of acquiring and possessing Property, and pursueing and obtaining Happiness and Safety.” —George Mason. Virginia Declaration of Rights, May, 1776. |

The words of George Mason (1725-1792) have inspired generations of Americans and others throughout the world. Mason was among the first to call for such basic American liberties as freedom of the press, religious tolerance and the right to a trial by jury.

The words of George Mason (1725-1792) have inspired generations of Americans and others throughout the world. Mason was among the first to call for such basic American liberties as freedom of the press, religious tolerance and the right to a trial by jury.

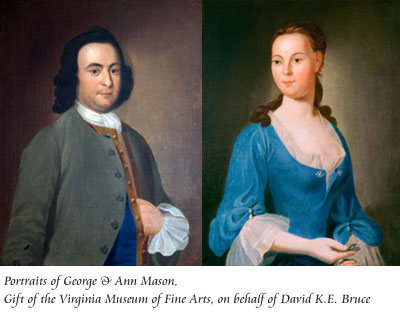

George Mason was born in 1725 to George and Ann Thomson Mason. Their first son and a fourth generation Virginian, Mason lived with his family on a Fairfax County Plantation. His father tragically drowned in a boating accident when Mason was ten, and his mother was left to raise George and his two siblings alone. After studying with tutors and attending a private academy in Maryland, at age 21 Mason took over his inheritance of approximately 20,000 acres spread across several counties in Virginia and Maryland. Four years later, in 1750, Mason married 16 year old Ann Eilbeck with whom he had nine surviving children. Mason adored Ann and was devastated when she died in 1773 at the age of 39. Relying on his eldest daughter to help run the domestic side of the plantation's operation, Mason remained a widower until 1780 when he married Sarah Brent.

Although highly respected by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, Mason did not aspire to join his peers in public office. When he was asked to take Washington's seat in the Virginia legislature, a slot vacated when Washington was named Chief of the Continental Army, Mason reluctantly agreed. In 1776 he was Fairfax County's representative to the Virginia Convention and was appointed to the committee to draft a “Declaration of Rights” and a constitution to allow Virginia to act as an independent political body.

Complaining about the “useless Members” of the committee, Mason soon found himself authoring the first draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights. Drawing from the Enlightenment philosopher John Locke, among others, Mason asserted, “That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights….among which are the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.” This document was the first in America to call for freedom of the press, tolerance of religion, proscription of unreasonable searches, and the right to a fair and speedy trial.

In 1787, Mason was chosen to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, where he was one of the most vocal debaters. Distressed over the amount of power being given to the federal government and the Convention's unwillingness to abolish the slave trade, Mason refused to sign the Constitution. One of three dissenters, Mason's refusal to support the new Constitution made him unpopular and destroyed his friendship with Washington, who later referred to Mason as his former friend.

Mason's defense of individual liberties reverberated throughout the colonies, however, and a public outcry ensued. As a result, at the first session of the First Congress, Madison took up the cause and introduced a bill of rights that echoed Mason's Declaration of Rights. The resultant first 10 amendments to the Constitution, also called the Bill of Rights, pleased Mason, who said, “I have received much Satisfaction from the Amendments to the federal Constitution, which have lately passed…” Invited to become one of Virginia's senators in the First US Senate, Mason declined and finally was able to retire to Gunston Hall, where he remained until his death on October 7, 1792.

Learn more about George Mason and his family.

Visit the George Mason Memorial page at the National Park Service web site.

George Mason

George Mason